Ashes excuses; Hapless Amateurs v Bastard Bankers; The limits of Tom Harrison; Esports Economics; Inside TikTok's gaming move; Sportico's Twitter list; Private schools selling 1957

The newsletter of the podcast

Thanks to Corey Leff (aka John Wall Street) for including me on Sportico’s Top 50 Twitter Follows for 2022. The list has got some good names on it.

To understand esports, you have to understand the Asia market, and btw stop referring to it as the Asia market

This week UP217 goes inside Moonton Games, the mobile gaming colossus that was bought by TikTok owner ByteDance in 2021 and are the pioneers of MOBA Gaming and in particular Mobile Legends: Bang Bang World Championship

Guests: Ajay Jilka, Director of Regional esports partnerships of Moonton Games, and Mike Wragg, Nielsen Sport’s Managing Director for Asia Pacific who is also the company’s International Head of Strategy Consulting and Research.

What we talked about:

What Moonton does, who it does it to and the implications of its takeover by ByteDance/TikTok.

Enduring Asian gaming cliches

The absurdity of viewing Asia as one homogenous marketplace.

The potential of econometric modelling, sales ROI dispersal, attribution error and causation v correlation.

Is esports just a demographic targeting thing?

The specificity of esports sponsorship v the vague promise of programmatic.

The ongoing implications of a mobile first content economy: McKinsey research on Generation Z in Asia found that 20 to 30 percent of this generation spends more than six hours a day on their mobile phones, voraciously consuming video content.

What do sponsors get back from streamers and esports influencers that they don’t get from other forms of marketing, other than simple demographic targeting choices?

The limits of Tom Harrison

England cricket’s awful Ashes failure has prompted questions as to causes and blame.

In English cricket, this road leads to Tom Harrison.

The ECB CEO was a guest on the podcast (UP161, recorded remotely), and he’s a member of the UP WhatsApp Group, but rarely contributes: I’ve no skin in the Tom Harrison game.

I mention this because some of what follows seems to defend Harrison against the accusation that he’s the architect of England’s catastrophic performance in Australia this winter.

I just think that’s too easy a story.

The Hapless Amateur and The Bastard Banker

Coverage of sports governing bodies veers between two poles.

The Hapless Amateur

Unofficial Partner is about the sports business, and much of the running commentary comes from people with something to gain from a change in the status quo: Creative destruction; greed is good; p/e brings a ruthless devotion to process but you don’t want to get stuck in a lift with one, etc.

If you’re flogging an abstract noun - data, entertainment, tech, innovation - or you have a specific product in the marketplace - an analytics black box or some web3 jpeg bollocks - NGBs, and people like Tom Harrison, are the gatekeepers, the problem, the machine against which you rage. The blob.

The Bastard Banker

When you leave the #Sportsbiz filter bubble, the caricature of Tom Harrison shape shifts from Hapless Amateur to Bastard Banker. And he doesn’t get any more popular.

The Bastard Banker is an amoral short term grifter who chooses to misunderstand the broader purpose of sport beyond financial gain. Etc.

See Barney Ronay’s piece here as an example.

See also: Andrew Miller went full Bastard Banker on ESPNCricinfo, evoking the financial crisis and the collapse of Lehman Bros.

To both groups, Tom Harrison - reassuringly perhaps - remains the problem to be solved: The cricket people think he’s money obsessed and the money people think he’s too conservative and beholden to the past.

The Bonus Story is Harrison’s exposed flank

The Bastard Banker requires us to think dark thoughts about incentives: that personal greed shapes corporate decision making.

The traditional NGB comms defence to this accusation is reinvestment, as put by Matt Rogan, co-founder of Two Circles:

Matt’s right, the money does flow back in to the game. And the ECB/Tom Harrison has greater influence than most governing bodies, because it owns the whole world of cricket within the UK, from club to pro, cups and leagues, counties and national teams.

But the sew/reap virtuous circle is breached by Ali Martin’s excellent scoop in The Guardian, revealing the £2.1m bonus awarded to Harrison and other ECB execs relating to the launch of The Hundred:

Tom Harrison and a group of senior executives at the England and Wales Cricket Board are poised to share a projected £2.1m bonus pot despite making 62 job cuts last year in response to the Covid-19 pandemic.

The most recent ECB accounts show that a five-year Long-Term Incentive Plan is due to be settled in cash in 2022, with the Guardian having learned that Harrison, the board’s chief executive who was paid £512,000 last year despite a voluntary pay cut, and Sanjay Patel, managing director of the Hundred, are among its intended recipients.

From here it’s a short hop to opportunity cost: did the bonus incentivise Harrison to prioritise The Hundred over The County Championship and thus short term gain (white ball) over long term development (red ball)?

Probably.

But the story of Tom Harrison’s bonus is a microcosm of the public-private questions that will dominate the sports business conversation over the next decade as more governing body sell stakes to private equity.

The unexciting reality of limited power

It’s absurd to compare the head of England cricket to the most powerful job on earth. So let’s do that.

Here’s what Barack Obama learnt when he became POTUS.

“I didn’t appreciate how weak the presidency is until I was president”

OBAMA: What I didn’t fully appreciate, and nobody can appreciate until they’re in the position, is how decentralized power is in this system. When you’re in the seat and you’re seeing the housing market collapse and you are seeing unemployment skyrocketing and you have a sense of what the right thing to do is, then you realize, "Okay, not only do I have to persuade my own party, not only do I have to prevent the other party from blocking what the right thing to do is, but now I can anticipate this lawsuit, this lobbying taking place, and this federal agency that technically is independent, so I can’t tell them what to do. I’ve got the Federal Reserve, and I’m hoping that they do the right thing—and by the way, since the economy now is global, I’ve got to make sure that the Europeans, the Asians, the Chinese, everybody is on board." A lot of the work is not just identifying the right policy but now constantly building these ever shifting coalitions to be able to actually implement and execute and get it done.

Or, to quote Obama’s predecessor George W Bush:

"If this were a dictatorship, it'd be a heck of a lot easier."

It’s not a huge jump to suggest that if the president of the US is limited in his ability to deliver change, the same is true of the bloke who runs a sport NGB.

This is deeply frustrating, because it reduces the righteous thrill we get from shitkicking the people in charge.

Build: All decisions are a response to previous decisions

A quick mention of institutional memory.

Every organisation has one and I’ve come to think the ECB is affected more than most.

Talking to Harrison on the podcast, I suggested that The Hundred was a reaction to failures by previous ECB regimes to capitalise on the T20 opportunity.

More generally though, many people in professional cricket mistakenly believe the past holds answers to future challenges.

The Ashes debacle is revealing, because of where we go for simple answers - past TV deals and private schools, neither of which do much for me.

Can we move beyond 2005 yet?

The ECB’s institutional memory is dominated by 2005 And All That, when the Giles Clarke and David Collier regime sold the entire live cricket inventory to Sky.

Hear UP 145 with former ECB head of commercial Terry Blake and David Brooks of Channel 4:

Terry Blake: “They actually only got £55 million a year. So for £10 million a year more - which no doubt helped Giles Clarke secure his chairmanship from the counties - they moved it off free-to-air television altogether.

Imagine the audiences that would have grown and the interest we would have had at the grassroots and club cricket and school cricket had we stayed on free to air…imagine how big the audience would have become and how much more we could have done with the sport by 2011, 2012, when we got to number one in the world.

David Brooks: The myth that’s been perpetuated in the press has been that moving cricket off free to air and onto pay has been in some way the salvation of cricket’s finances, but actually it was 10 million pounds a year. That’s not what people think. People imagine it was untold riches.

Brooks references Trevor East, then of Sky Sports.

Trevor East came out with that famous line at the time, in response to accusations that Sky had stolen cricket from the public said, “Well, we didn’t steal cricket. The ECB gave it away”. And that was true.

But the 2005 decision was in itself a reaction to previous ones.

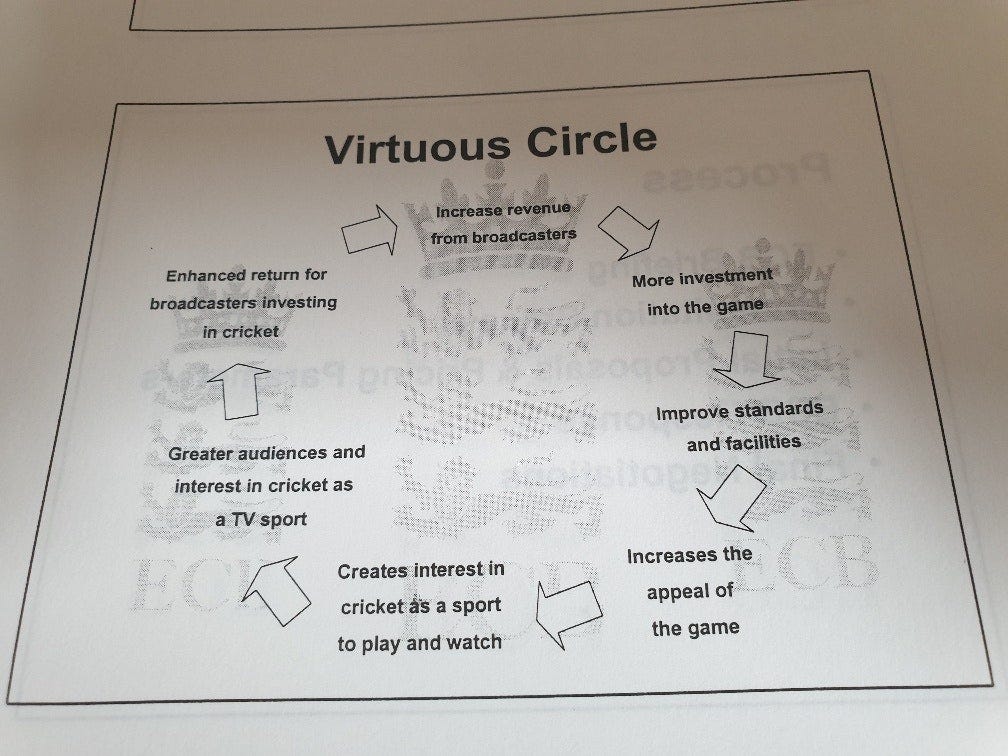

The 1998 virtuous circle needs an update

As noted in a previous UP Newsletter, this 1998 report reveals the ECB’s state of mind during this period, when all media rights conversations were dominated by the rise of Sky Sports.

The key page in the document is the one below.

The virtuous circle is the intellectual framework used by every generation of sports marketing executives since the launch of satellite television.

The trauma of watching England’s top order has focused minds on various parts of this diagram.

My view is that this framework is simplistic, over promises and needs updating to make it relevant to today’s media habits, audience behaviours and incentives in play for the companies seeking to meet them.

See also: Test cricket, cold product.

Format change needed.

27 of the last 88 Ashes Tests will essentially have been cold product, nothing riding on them but pride and broadcasting contracts.

Hear UP181 on sports formats and the business of jeopardy, with Omar Chaudhuri and Ben Marlow from Twenty First Group.

I was really impressed by their Quality-Jeopardy-Connection model. And I’d certainly take it over the ECB’s 1998 effort.

Final point: I hate private schools but they’re not the point here

Jonathan Liew said that Ian Bell was the last world class state educated England test batsman.

This was a way in to the question of talent pathways and access.

See also:

As a former state school pupil and teacher I’m there in sentiment, but there’s a niggle.

Caveat: Every conversation about education degenerates in to autobiography.

Private schools promote cricket because they think it’s in their commercial interests to do so.

Private school marketing sells a version of the past, when children wore blazers and caps, England had an empire and poor people didn’t talk back.

They go big on cricket because it talks to this story more than other sports - it’s no coincidence that the last time the England test team were unequivocally the best in the world was in late 1950s.

This tweet is intended to make me angry at the unfairness of it all.

But it doesn’t solve cricket’s problems.

Of course kids from private schools have an advantage.

But I hate to break it to you, this is not limited to access to the England team.

It turns out that private schoolkids get a disproportionate number of great gigs when they leave school. They sit in Cabinet, get nominated for Oscars and dominate TeamGB.

Sack Tom Harrison or don’t sack Tom Harrison, either way my faith in his ability to fix this problem is limited to say the least.

The reality of life on Tour

Meg MacLaren (UP194) is one of the most insightful pro athletes working across any sport.

Pull Quote: Freemium games tie playtime to revenue

The Economist called for gaming firms to share their player data to alleviate fears of user addiction (spoiler, they won’t). But this is a paragraph that merits further discussion.

The motive arises from a business-model shift. In the old days games were bought for a one-off, upfront cost. These days, many use a “freemium” model, in which the game is free and money is made from purchases of in-game goods. That ties playtime directly to revenue.